Coticules are extremely versatile hones. When used with slurry, they remove steel quite rapidly. When used with water they are among the very best options for finishing a razor's edge. The challenging part of honing a razor on nothing but one Coticule is bridging the small gap of keenness that lies between the edge left by the slurry and the sharpness required to finish on water. The method, here presented, provides a simple yet elegant solution for this issue.

To keep matters as uncomplicated as possible this method relies on as little honing test as possible. For this reason, the guideline must be followed strictly.

Required Items.

- a straight razor in undamaged condition. It may be dull, or not shaving well for whatever reason, as long as there are no flaws at the edge that can be seen with the naked eye. (no missing chips or obvious corrosion).

- a serviceable Coticule. It must be lapped flat and have chamfered or rounded edges.

- a Coticule slurry stone.

- a cup of water

- some electrical insulation tape

- a glass jar or a drinking glass

Method.

Step 1. Make sure that the razor does not shave arm hair. If it does, run the razor without any significant pressure, edge down, over the bottom of the glass jar. Check again to make sure that it no longer shaves arm hair.

Step 2. Raise slurry on the Coticule. Sprinkle some water on the surface and rub with the slurry stone till the fluid has a milky consistency.

Step 3. Place the razor on the Coticule and perform half X-strokes, with the index finger pressing down at the middle of the razor, near the spine (apply slight pressure with the finger and not with the wrist). Perform diagonal back and forth motions without flipping the blade. Count 30 laps. Flip the blade and copy 30 back and forth strokes on the other side.

Check if the razor shaves arm hair. If not, repeat the 30 laps on both sides, same fashion. Continue doing this, till the razor manages to shave arm hair. Only then, proceed to the next step. You may have to repeat this 2 to 20 times, depending on the initial condition of the razor. If it takes a long time, try keeping an eye on the width of both bevel sides. If they start showing unequal width, spend some extra laps on the narrowest side. On most undamaged edges, with a normal bevel width, it won’t take longer than 2 or 3 times 30 laps.

Step 4. Once the razor shaves arm hair, refresh the slurry, make it slightly thinner than before.

Perform about 30 regular X-strokes with as little pressure as you can while steadily guiding the razor.

This amount is given for a typical 6"X2" (15cmX5cm) Coticule. Adjust the lap count according to the particular Coticule.

Step 5. Add one layer of electrical insulation tape to the spine. Rinse the razor. Do not rinse the Coticule but add a splash of clear water. The slurry should be quite watery. Perform 30 X-stroking laps.

Step 6. Completely rinse the Coticule and sprinkle clean water on top. Rinse the razor. Finish with 50 laps, using only clear water on the hone. Remove the tape and gently dry the razor with a piece of tissue paper.

Step 7. Strop the razor on a good hanging strop. Keep the strop reasonably taut and apply light pressure on the razor, just enough to develop a light drawing sensation. Strop 30 laps on a clean linen and 60 laps on clean leather.

Elaboration.

There are two counterintuitive features to this method. The first is to dull the edge prior to aiming for flat and completely developed bevel faces, which is a crucial condition to be met, before the edge can be refined to a comfortable shaving keenness. The reason for starting with a razor that does not shave arm hair, is to take the guesswork out of knowing when the aforementioned goal is accomplished. Razors often have arc-shaped bevel faces, due to the use of pasted strops for maintaining the shaveability of the edge. Eventually the arc introduced in the bevel of the razor becomes so curved that the shaving comfort is compromised. At that point, it is time for honing, however the edge is still capable of shaving arm hair. When we remove this shaving ability in the slightest of ways, by running the edge once over a glass surface, we know with absolute certainty that the edge will not pass that test again before the bevel faces are completely flat and extending fully. A second advantage is that with this method, also all small blemishes accumulated by edge deterioration, will be gone. Our new edge will live in fresh and uncompromised steel.

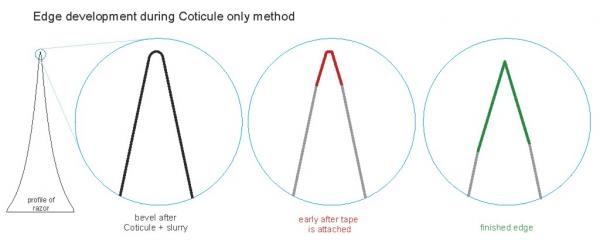

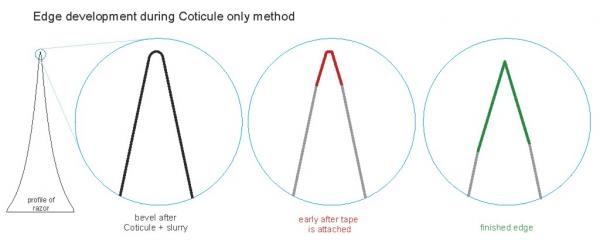

The second feature that might seem counterintuitive, is the application of one layer of tape halfway through the honing process. Slurry on a Coticule abrades steel with ample speed, but it is also somewhat detrimental for the extremely fine tip of the edge. The impact of the tip with the abrasive garnets in the slurry has a rounding effect. At the same time there is also a sharpening effect due to steel being removed of the bevel faces. At a certain level on the keenness scale, the dulling effect neutralizes the sharpening effect. One could hone the razor into oblivion on the hone with slurry, never would it take a keener edge than that predetermined level.

When no slurry is used on a Coticule, the garnets stay safely embedded into the surface of the hone, only protruding with a small part of their body. They quickly loose their bite and no fresh garnets are exposed to continuously rejuvenate the cutting force of the hone. As a result the Coticule becomes a very slow and shallow polisher, superior for smoothing, but almost useless for refining the edge.For this reason, simply stepping up from a Coticule with slurry to one with merely water, will not deliver good keenness. Gradually diluting the slurry helps, but it is an inconsistent method that requires a lot of honing skills for vacillating success.

But there is a way for exponentially boosting the performance of extremely slow hones. If the Coticule, used with water, is allowed to work on a narrow strip near at apex of the blade, it will remove enough steel to refine the edge, gradually slowing down as a new flat region grows. One layer of tape added to the spine is all it takes to divert all refining action to the tip to the bevel. Because the new, secondary bevel is only altered by the smallest possible degree, it must be allowed enough width, in order to refine the initial bevel. A drawing should clarify this:

An extensive number of tests with different Coticules on different razors has revealed that the most consistent results are reached when doing a small amount of work with a very watery slurry before finalizing on the Coticule with clean water. A bit of experimentation will reveal the best ratio for each individual stone.

23Likes

23Likes LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks