Results 21 to 30 of 48

Thread: IXL Washington Works

-

04-22-2014, 02:28 PM #21Historically Inquisitive

- Join Date

- Aug 2011

- Location

- Upstate New York

- Posts

- 5,782

- Blog Entries

- 1

Thanked: 4249

-

The Following User Says Thank You to Martin103 For This Useful Post:

sharptonn (04-22-2014)

-

04-22-2014, 02:33 PM #22

-

04-22-2014, 03:44 PM #23

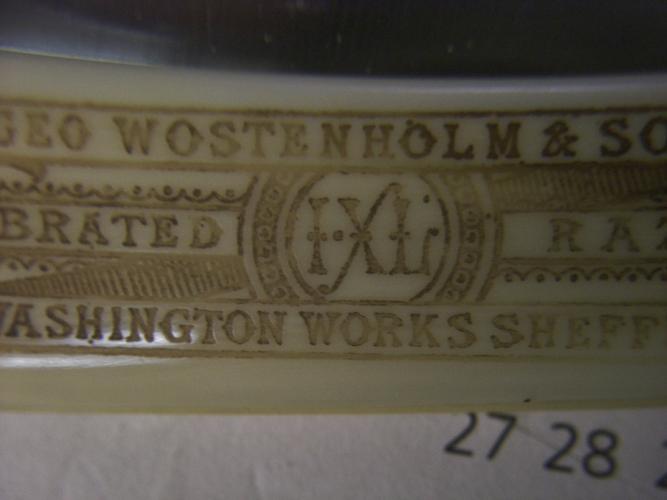

Scrimshaw, by hand, is pretty primitive under magnification. This is very precise! like machine engraving?

"Don't be stubborn. You are missing out."

"Don't be stubborn. You are missing out."

I rest my case.

-

04-22-2014, 04:02 PM #24Historically Inquisitive

- Join Date

- Aug 2011

- Location

- Upstate New York

- Posts

- 5,782

- Blog Entries

- 1

Thanked: 4249

It does look very precise, perhaps a metal stamp, burned into the ivory.

-

The Following User Says Thank You to Martin103 For This Useful Post:

sharptonn (01-27-2016)

-

04-22-2014, 04:03 PM #25Senior Member

- Join Date

- Apr 2008

- Location

- Essex, UK

- Posts

- 3,816

Thanked: 3164

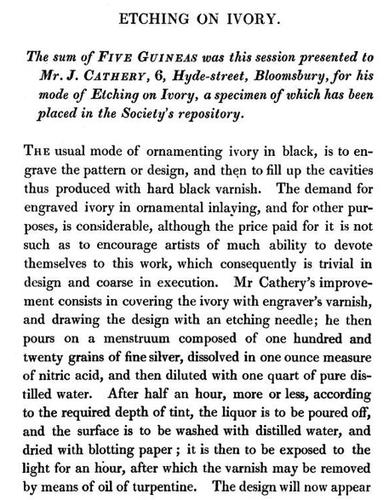

The accepted technique was actually to lay a resist on the ivory, then use and acid or some similar 'biting' fluid to eat away the exposed parts. The resist was then removed, and a layer of black enamel - or even various colours - were rubbed into the etched lines to enhance them.

Resists were made on paper using a form of glue that hardened on exposure to uv light - regular open sunlight. The glue was mixed with a reagent to bring about this hardening, which is not the same as simple drying. The ultra-thin papers were sold or made in house, wetted, and placed in position on the ivory (or the blade). Once the glue had hardened water was used to remove the paper - it was so thin it rubbed off easily, but water no longer rendered the hardened glue (or 'gum') tacky. Then the area was either immersed in acid, or a small dam was made of beeswax around the area, and acid brushed on. Once 'bitten' deeply enough the resist was removed with spirit.

There were variations to the basic technique including pre-cut rubber stamps that were dipped into the resist and then pressed onto the scale or blade, leaving the resist behind to harden.

There were also other resists in the form of varnishes or waxes that were worked with the point of a pin to reveal the substrate to be etched. This was more akin to scrimshaw, even though it too varied quite a bit, and was obviously inferior to other techniques when a good number of copies had to be made. All said and done, though, the totally handworked examples were far more crisp and sharp in appearance to the papers and rubber stamps!

The following is from an 1825 pamphlet issued by the Royal Society of Arts:

The silver nitrate certainly does work and has a two-fold reaction. Firstly it is caustic - if strong enough it can eat into and blister the skin (hence its old name - 'lunar caustic'), it can be used to kill the nerve in bad teeth, and on exposure to sunlight it goes a brown/black colour that is more or less indelible. I used to use it in photography when making collodion wetplates - the plate was sensitised by immersing it in lunar caustic then popping it into the camera back, still dripping wet. Of course, it got all over your hands and fingers. The moment you went into natural light your skin in the affected parts went back, and stayed that way until the skin layers grew out - some considerable time.

In the 1860s when wetplate photography was at an all-time height (people were photographing red indians, travelling cowboy shows and civil war soldiers like there was no tomorrow - no doubt, for many of the soldiers there was indeed no tomorrow and their likeness in a piece of glass plate or tin plate was all that remained for their families) these marks earned fledgling photography the title of 'The Black Art' - it was not long since the invention of the Daguerreotype and the two forms co-existed for some time until the ensuing madness from breathing in the vapours of heated mercury used to develop the silver image put people off the former.

But I digress....

Regards,

Neil

PS: nearly forgot to congratulate Tom on the aquisition of another splendid oldie and a stunning resto job - getting used to that with Tom, though!Last edited by Neil Miller; 04-22-2014 at 04:12 PM.

-

The Following 5 Users Say Thank You to Neil Miller For This Useful Post:

engine46 (08-05-2015), Leatherstockiings (04-22-2014), sharptonn (04-22-2014), Wullie (04-30-2014), WW243 (04-24-2014)

-

04-22-2014, 04:21 PM #26Senior Member

- Join Date

- Dec 2011

- Location

- I'm Gonna Spend Another Fall In Philadelphia

- Posts

- 2,024

Thanked: 498

All that bloody work for so little reward (financially speaking) What was the going rate for a razor of this caliber? A few shillings I suspect?

-

The Following User Says Thank You to Tarkus For This Useful Post:

sharptonn (04-22-2014)

-

04-22-2014, 04:50 PM #27

-

04-22-2014, 04:51 PM #28Historically Inquisitive

- Join Date

- Aug 2011

- Location

- Upstate New York

- Posts

- 5,782

- Blog Entries

- 1

Thanked: 4249

-

The Following User Says Thank You to Martin103 For This Useful Post:

sharptonn (04-22-2014)

-

04-22-2014, 04:53 PM #29

-

04-22-2014, 05:07 PM #30Senior Member

- Join Date

- Apr 2008

- Location

- Essex, UK

- Posts

- 3,816

Thanked: 3164

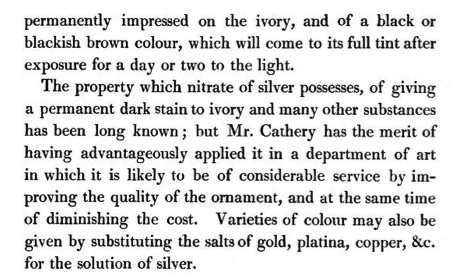

From the 1902 Pacific Hardware & Steel Catalog:

The pics not much, but the razor was available with 'white flat handle, as well as 'ivory flat handle', blades 'full crocus polished'.

The ivory version was $36 per dozen, so $3 a piece to the trade. No doubt the public paid double that, so say $6. From a 1902 us dollar/pound sterling exchange rate guide, $6 usd is equal to £3.55, equal to £3 11 shillings or 31 shillings in sterling.

A labourer/cleaner in 1902 would perhaps be paid from $1.00 usd to $1.50 usd a day, so would have to work at least four days and probably longer to afford this particular razor - seems a fair lot of money to me!

However, if $6 usd represented a 100% mark-up to the re-seller, who bought it from another re-seller (Pacific Hardware) who bought it from the maker (Wostenholm) then the true value of the razor begins to emerge. Say Pacific Harware & Steel (merged with Baker & Hamilton in 1918 to form Baker, Hamilton & Pacific, housed in a 1905 building that is now a landmark in San Francisco) put 100% on for example, then they paid $1.50 in order to offer it for for $3 usd. Wostenholm would perhaps put 100% on, so the razor cost them 75 cents. Out of a portion of that the workers were paid, which is beginning to stink of sweat-shop practices like those still seen in poor eastern countries, particularly when major makers insisted on having a margin of error to fall back on, so a dozen razors produced by the workers had to have another three thrown in free of charge in case of damage, returns etc, although this was more the practice of an earlier time.

Regards,

NeilLast edited by Neil Miller; 04-22-2014 at 05:19 PM.

-

131Likes

131Likes LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote