Results 1 to 10 of 12

-

04-18-2013, 01:30 PM #1Historically Inquisitive

- Join Date

- Aug 2011

- Location

- Upstate New York

- Posts

- 5,782

- Blog Entries

- 1

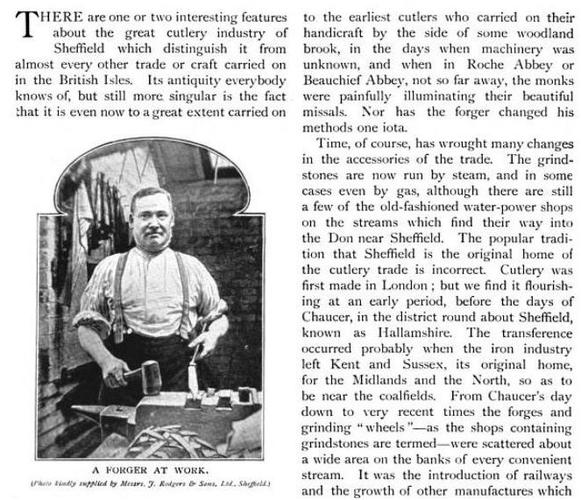

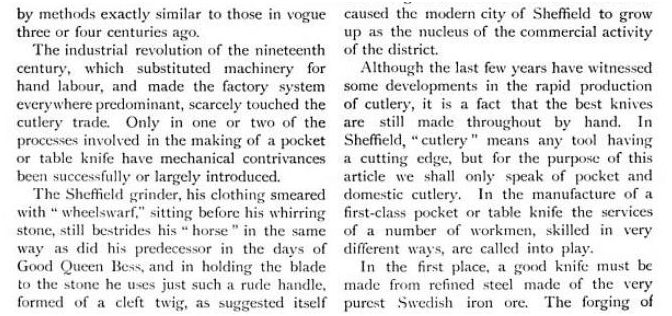

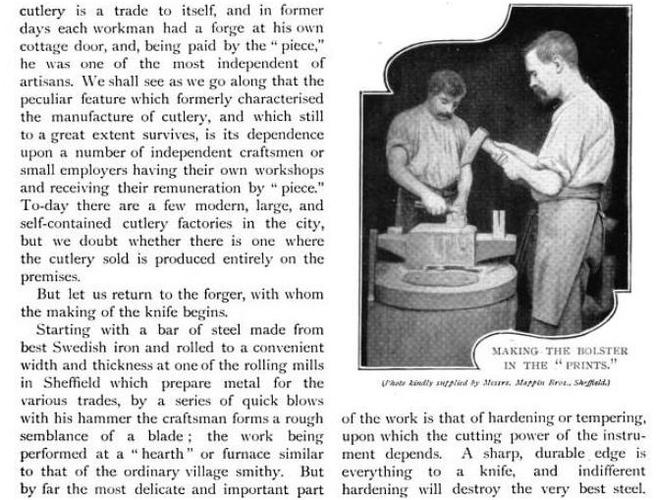

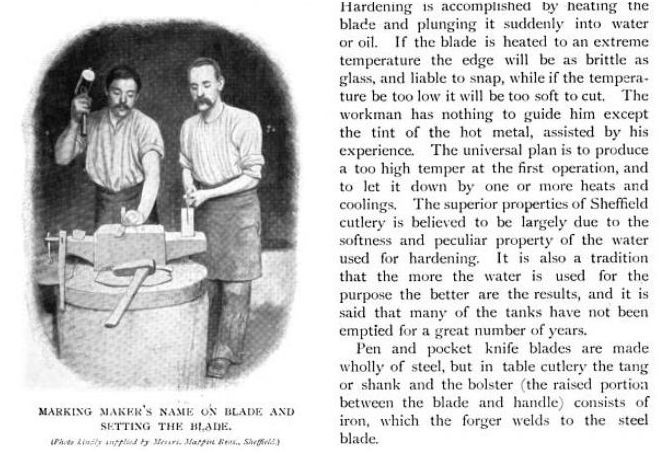

Thanked: 4249 Britain at work, The Cutlery Industry, by John Whitaker 1902

Britain at work, The Cutlery Industry, by John Whitaker 1902

Britain at work, The Cutlery Industry, by John Whitaker 1902.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Last edited by Martin103; 04-18-2013 at 01:33 PM.

-

-

04-18-2013, 01:38 PM #2Historically Inquisitive

- Join Date

- Aug 2011

- Location

- Upstate New York

- Posts

- 5,782

- Blog Entries

- 1

Thanked: 4249

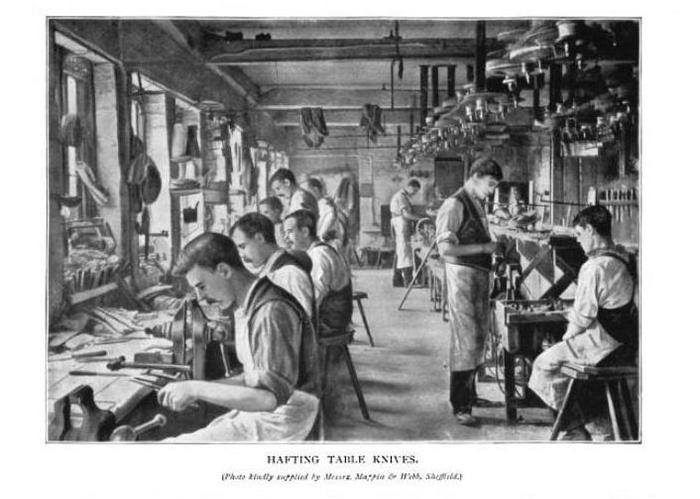

And the rest of the article bellow.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-

The Following 4 Users Say Thank You to Martin103 For This Useful Post:

bongo (04-22-2013), Geezer (04-20-2013), Lemur (04-19-2013), Voidmonster (04-18-2013)

-

04-19-2013, 02:38 PM #3

Thanks for posting this Martin, I always find these fascinating to read.

The article prompted a couple of thoughts:

- I wonder what the average worker made doing piecework for W&B or any of the other Sheffield manufacturers relative to the average wage at the time. I assume it was considered "skilled work" and they were craftsmen rather than laborers but I wonder how their wages compared.

- The article mentions "men and boys" being employed in the trade, I wonder how old the youngest workers were. I'd expect since it was considered a craft they were apprentices, I'm curious what work they actually did.

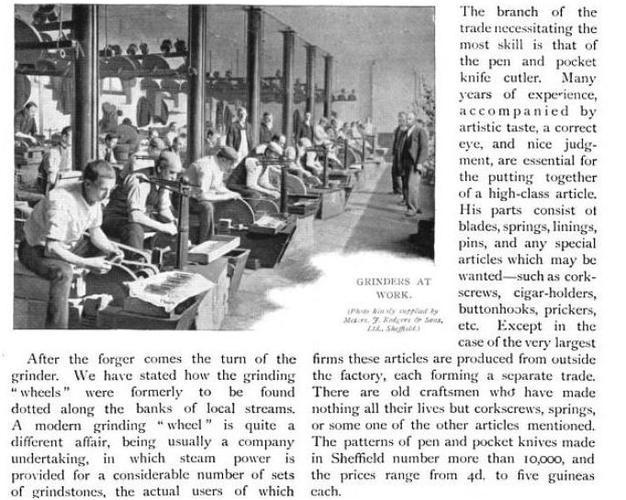

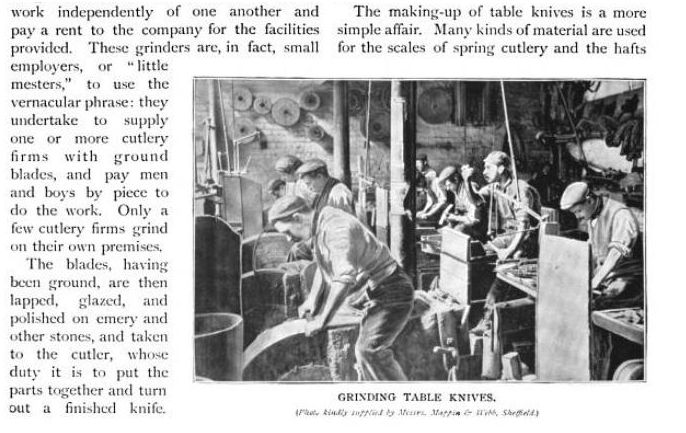

- That really does look like back breaking labor. "Nose to the grindstone" takes on new meaning! In a picture you posted a while back, the belts driving the grindstones ran through channels in the floor and the workers sat on benches and bent down to use them. Given what was probably the prevailing workday at the time (10 hours or so) that's a really tough way to make a living.

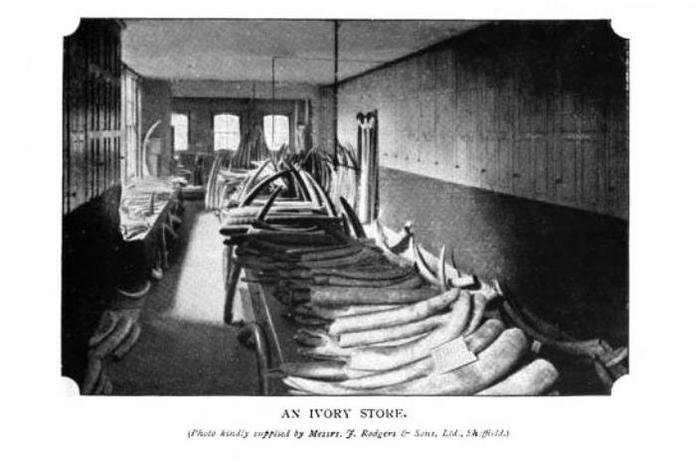

- The picture of the ivory store was amazing - that's a lot of elephants!

Thanks again for posting.Greg

-

04-19-2013, 03:05 PM #4Historically Inquisitive

- Join Date

- Aug 2011

- Location

- Upstate New York

- Posts

- 5,782

- Blog Entries

- 1

Thanked: 4249

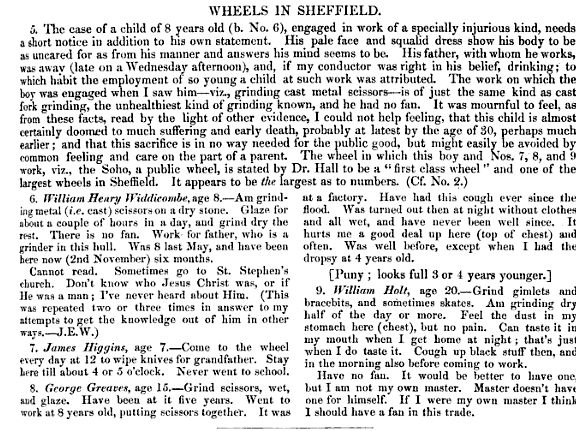

As far "men and boys", here a table from sheffield children employment commision. And an example of how young they were when they starting to work.

-

The Following 4 Users Say Thank You to Martin103 For This Useful Post:

Geezer (04-20-2013), Lemur (04-19-2013), RezDog (04-19-2013), Weaselsrippedmyflesh (04-19-2013)

-

04-19-2013, 03:53 PM #5Historically Inquisitive

- Join Date

- Aug 2011

- Location

- Upstate New York

- Posts

- 5,782

- Blog Entries

- 1

Thanked: 4249

Another pic of ivory from the London docks at the turn of the century.

-

04-19-2013, 08:36 PM #6

The question of wages is very complicated, and my understanding of it is still incomplete. While this is ostensibly describing Wade & Butcher, the structure was pretty much the same everywhere. It goes something like this:

The Butcher Brothers (Robert Wade died in 1825, and while his son ultimately did go on to be the American agent for the company, after 1825 'Wade & Butcher' is only a trademark, not the company name) owned the wheel or factory (several different ones over time, actually) where their goods were produced. They also owned the tools within it (grindstones, mechanical hammers, etc). In order to make cutlery, they rented that space to men who then hired small teams of specialists. Razor making broke down into three branches: forgers, grinders and 'setters-in' (the guys who took the blade and the premade scale-parts and assembled the final product, including sometimes polishing).

Those wages in 1850 were:

- 24-33 shillings for a forger

- 21-48 shillings for a grinder

- 15-30 shillings for a setter-in

It's useful to understand that these weren't decimal numbers of money. At the time, 20 (s)shillings made a pound and 12 (d) pennies made a shilling.

But that's not really the full picture. Each of those guys had to pay rent on the work space, the tools and the power to run those tools (including gas for light and heating), he then also had to hire and pay assistants as well as purchase the materials to make the goods. And then, fairly regularly, they were paid in truck in part or in whole. That means that they were given grain, coffee or sometimes cheap cutlery instead of wages.

There were also a lot of women and girls working in the industry. In Sheffield, 1865, there were 765 women and girls working in the cutlery industry (compared to 13,339 men and boys).

That covers wages (more or less), but the question of age and apprentices is also complicated.

In 1814 the Cutlers Company of Hallamshire lost their monopoly control over the industry. Prior to that, anyone striking their own mark on cutlery had to pay dues and abide by the rules of the company, which theoretically included hard limits on the number of apprentices and what apprentices were allowed to do and not do.

Apprentices were normally taken on between 8 and 10 and the normal course was 7 years (in the razor trade, others varied). Some were apprenticed as young as 6.

A cutler was bound by guild law to have only one apprentice at a time, a law whose enforcement was ... lax. John Barber, father of the more familiar John Barber, had 12 apprentices. He fed them only stale food because he believed that would suppress their appetites thus allowing him to feed them considerably less food. Being an apprentice could be appallingly difficult. Very, very few of the children who became apprentices completed their years. Many joined the navy instead because it offered a better life (and if you know much about the navy in that time, you have an idea of what that means).

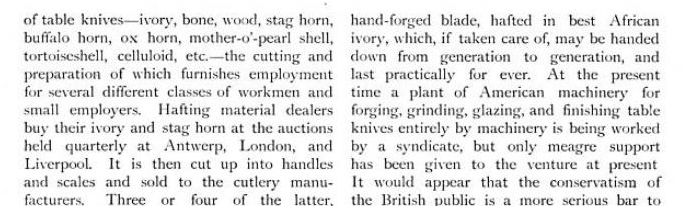

In the razor trade, apprentices usually started off polishing blades -- so when you admire the shine on your old Sheffield razor, just remember it was a child that was responsible for that.

Life for the adults in the industry wasn't so hot either.

Grinders had the worst of it by far because of the multiple dangers of the grinding wheel. The most immediate being that the large sandstone wheels had a habit of exploding, fairly regularly killing workers. If they weren't killed by the wheels, they were killed by the dust (some parts of grinding required grinding dry, and thus filling the air with stone particulates, which lead directly to silicosis or 'grinders asthma'). The average life expectancy of a grinder was about 34. It wasn't until almost 1900 that they finally got sufficient ventilation to start really improving that.

Razor grinders were in the middle of the pack on that front, with fork grinders having the worst health of all.

It was fairly common for out-workers (that is, the crews hired by the foremen) to actually owe their employers instead of making money, and as a result many workers took on second and third jobs to pay for first and second.

The work wasn't steady -- these factories didn't produce goods when they didn't have orders -- and so foremen often took commissions for outside work which they performed at the factory. It's entirely possible that your Wostenholm razor was made by a guy who worked for Joseph Elliot on grindstones owned by William and Samuel Butcher.

For a good long time there were actually prohibitions against 'night work' because everyone agreed it was hard to do quality work in the dark, but gaslamps eventually overcame that. Work days varied considerably, depending on the amount of work that was available -- remember, there was not a constant demand for these goods, it waxed and waned, and when it was on the wane, the workers resorted to farming.

That's just Sheffield, though. There were a lot of other places producing good cutlery, and work conditions varied wildly.

An excellent book on the subject (if a bit dry) is Godfrey Issac Lloyd's The Cutlery Trades. The vast majority of the information I've just posted is a breezy summary of what that book goes into much greater depth on.Last edited by Voidmonster; 04-19-2013 at 08:38 PM. Reason: The first draft of the post used Wostenholm as an example, but I changed it midway and had to excise all the George.

-Zak Jarvis. Writer. Artist. Bon vivant.

-

The Following 3 Users Say Thank You to Voidmonster For This Useful Post:

Geezer (04-20-2013), Martin103 (04-20-2013), Weaselsrippedmyflesh (04-20-2013)

-

04-20-2013, 12:47 AM #7

Wow Voidmonster, what a wonderful detailed reply! Thanks so much for all of the information, very interesting.

Greg

-

The Following User Says Thank You to Weaselsrippedmyflesh For This Useful Post:

Voidmonster (04-20-2013)

-

04-20-2013, 12:54 AM #8

-

04-20-2013, 01:41 AM #9

I should also add to that that the workers weren't paid a wage, precisely, but were instead paid by the quantity of work they completed, called day-work. A single 'day-work' could be between 18 and 60 blades, depending on the size and complexity. Skilled forgers could make 16-20 day-works in a week.

The standard rates for that work were fixed in 1810 and continued on to at least 1910.

A forger made about 3 shillings per day-work, of which he paid about 1 shilling to his striker (if the work required two hands, which some razor work did).

So at the upper end of production, a forger might be producing 1200 blades a week and making 60 shillings a week. But again, you have to subtract rent and materials from that. Rent, for that work was about 4 pennies per-week. Numbers that high represent an absolute maximum, actual production and wages were likely to be considerably lower.

The other branches varied quite a bit more. Grinders did comparatively better, but had far worse lives and volatile trade unions to go with it. Setters-in were split into multiple sub-branches for hafting and pressing (all vintage horn scales were pressed, not cut and sanded, to shape). The setters-in also didn't have such clearly defined price lists and didn't make as much as the grinders or forgers.-Zak Jarvis. Writer. Artist. Bon vivant.

-

-

04-20-2013, 04:08 AM #10

Here are some figured\s to help put things into a perspective as to values in 1902.

A simple measure from the internet is 12 pence to the shilling, 20 shillings to the pound. A pound in 1902 was equal to a bit over a hundred dollars today.

That would make a shilling worth about five dollars in purchase power.

In the USA, a common wage was about a half to one dollar a day till 1940 or so. Inflation would make that about $27 dollars in purchasing power today. 6 day week and 312 days of work would have been about a $320 dollars a year equivalent in today's money. A small house then would have been about 1K.

This is where the difference gets wild.

http://www.measuringworth.com/uscomp...ativevalue.php

~Richard

-

The Following User Says Thank You to Geezer For This Useful Post:

Martin103 (04-20-2013)

23Likes

23Likes LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote