Results 171 to 180 of 188

-

02-27-2018, 02:51 AM #171Senior Member

- Join Date

- Feb 2016

- Location

- pennsylvania

- Posts

- 302

Thanked: 66

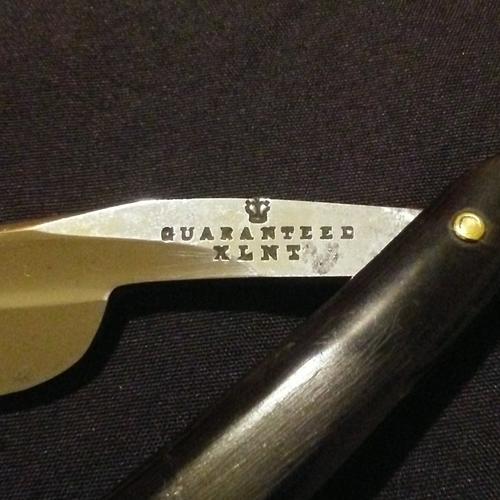

does this count?

-

The Following User Says Thank You to sloanwinters For This Useful Post:

sharptonn (02-27-2018)

-

02-27-2018, 02:54 AM #172

YEAH! That counts! BJ Eyre bought out Greaves. They milked the names often.

Beautiful razor.

-

11-01-2018, 01:05 PM #173

Last edited by MikeT; 11-01-2018 at 01:08 PM.

You must unlearn what you have learned.

Yoda

-

11-01-2018, 01:24 PM #174

They sure do look like the same identical grind.

Mike

-

11-01-2018, 01:39 PM #175Senior Member

- Join Date

- Dec 2012

- Location

- Egham, a little town just outside London.

- Posts

- 3,856

- Blog Entries

- 2

Thanked: 1083

Back in the day the same person could be making razors for a number of different manufactures on the same day.

-

The Following User Says Thank You to markbignosekelly For This Useful Post:

MikeT (11-01-2018)

-

11-01-2018, 01:41 PM #176

They do look very similar, just the tails have a different profile.

I wonder if there was a degree of re branding going on ? The razor blanks could have been sent to the same grinding hull, in the early days these would have been where there was a water supply, water was needed to turn the wheel providing the power.

Sheffield has a number of rivers where these were situated.Regards Brian

-

The Following User Says Thank You to 782sirbrian For This Useful Post:

MikeT (11-01-2018)

-

11-01-2018, 04:29 PM #177

So it's possible that there were the people making the blanks and then sending to a grinder. When were the stamps put on?

Did companies like Greaves & sons sub-contact out to various blade-smiths and grinders?

Seems they would not want to share a stamp, unless there were trademarks that various blade-smiths owned and allowed multiple companies like Greaves & sons, and marshes & shepherds in this case to use them?

?You must unlearn what you have learned.

Yoda

-

11-01-2018, 04:59 PM #178

Not only possible, that was quite an identity of the Sheffield trades for a long time. This may help answer your question:

(emphasis mine)The operation by manufacturers of self-contained factories, where all workers were employed directly on the owners' products, had always been alien to these trades. Where a manufacturer owned the premises, some men would devote most of their time to his work, but most rented space by the week, and worked on orders from manufacturers all over the town, including the owner of the premises.

In addition to these privately owned works, there were the 'public wheels', the owners of which had nothing to do with the trades beyond the renting out of space and power to individual workers. Furthermore, scattered throughout the town and its environs, there

were hundreds of small workshops, often in lean-to sheds, where outworkers worked up goods for a variety of manufacturers and merchants. As capital requirements were so small - it takes only "one and fower pence to make a cutler", independent production

was common and small master status the legitimate expectation.

It has been said that the early 19th century saw an increase in the number of larger, more integrated firms at the expense of the small scale, rented unit, which is seen as the emblem of handicraft practices and values. However, such conclusions often rely too heavily on the use of trade directories, which give undue emphasis to the 'works' of the larger manufacturers, whilst underestimating the unquantified masses of outworkers who could not afford a directory entry. A more fundamental criticism of this view however, lies in the traditional organization of the large firms: huge quantities of goods were still obtained from outworkers, whilst many inworkers were in reality, still semi-independent contractors. In 1844, a commentator on the cutlery trades stated that "there are several modes of conducting the manufacture, but the factory system is not one of them .... there is no large building, under a central authority, in which a piece of steel goes in one door and comes out at another converted into knives, scissors and razors. Nearly all the items of cutlery made at Sheffield travel about the town several times before they are finished.

From Chapter 1 (Sheffield manufacture pre-1870), from a PhD dissertation on the subject: http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/5990/1/259670_VOL1.pdf

-

-

11-02-2018, 03:55 AM #179

Hah!!!

That is incredible! Kinda blows my mind!

This whole time, though I've been aware of the "little masters" and such, in my mind were all these straight razor manufacturer legends.. Just pick a name.. And these powerhouses battling it out for dominion of the cutlery world.

Instead now I've got this much more diverse image, somewhat of an all out free for all battle with small time guys sneaking in and counterfeiting successful trademarks from some of the big guys...

It must have been beautiful chaos!

Hehehe

You must unlearn what you have learned.

You must unlearn what you have learned.

Yoda

-

11-02-2018, 07:59 AM #180

That's still not the right picture though. The social constructions of the cutlery trades did begin to change in the later 19th c, but in the early half at least the 'big guys' were still made up of the 'little guys', and it was not unusual for a little guy renting space somewhere to make some razors stamped from one company, then make some others stamped with someone else, with everyone's knowledge. So it wasn't a counterfeiting situation, it was the norm; you might have one company's factory housing workers making some products for them, some products for another company, and some other workers who lived out in the country might also be making products for that same firm. Here is another resource:

https://historicengland.org.uk/image...reat-workshop/

-

The Following 5 Users Say Thank You to ScienceGuy For This Useful Post:

32t (11-02-2018), bartds (11-02-2018), markbignosekelly (11-02-2018), MikeT (03-03-2019), outback (11-02-2018)

423Likes

423Likes LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote